By Paul Carrier

It’s late in the year 1314, and all is not well in France. Quite the opposite, in fact. And as bad as things are, history tells us they are about to get much worse.

Philip IV, the stern but competent king of France for close to 30 years, has died after disbanding the wealthy Knights Templar, whose leader placed a curse on Philip and his descendants. Philip’s son Louis, a self-centered, hotheaded and weak-minded fool plagued by anxiety attacks, has assumed the throne, but he is relying far too much on his manipulative uncle Charles, the late king’s brother.

Charles is out to destroy Enguerrand Marigny, Philip’s right-hand man and an indispensable administrator whose wisdom and experience the kingdom sorely needs during this time of transition. Marigny resents the effort to push him aside and fights back, in part by scheming to slow the election of a new pope, which Louis wants to expedite so he can annul his marriage to the adulterous Marguerite.

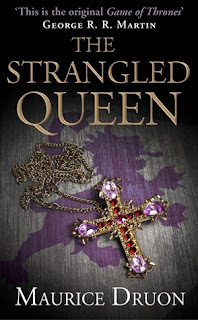

So opens The Strangled Queen, the second installment in Maurice Druon’s seven-part series of historical novels known collectively as The Accursed Kings. Written in French but available in English in paperback editions, the series has fans as diverse as George R. R. Martin and Vladimir Putin.

If The Strangled Queen sounds like a medieval soap opera (the title alone suggests as much), that’s not too far from the truth. What makes it compelling, though, in addition to Druon’s plotting and characterization, is the fact that the seemingly outlandish goings-on are at least loosely based on fact. In a list of some two dozen characters, Druon writes that only “a few extras” in the novel are fictional.

The people and plot twists in The Accursed Kings may be unfamiliar to American readers, but taken as a whole, the saga chronicles far more than a collection of historical footnotes. Druon focuses on the decline of the powerful Capet dynasty, which ruled France for over 300 years, and the start of the Hundred Years War, in which England’s House of Plantagenet fought France’s House of Valois for nothing less than control of France itself.

Druon, who died in 2009, had a knack for describing characters, even bit players, in quick but telling sketches. Take, for example, this depiction of Lormet, the slavishly loyal valet to Robert of Artois, a high-ranking nobleman related to the king.

“Unusually vigorous for his fifty years, all the more dangerous for his mild appearance, capable of anything in the service of ‘Monsieur Robert,’ and above all of obliterating noiselessly in a few seconds people who were an embarrassment to his master, Lormet, purveyor of girls on occasion and a great recruiter of roughs, was a rogue less by nature than from devotion; a killer, he had the affection of a wet nurse for his master.”

Druon is a bit florid at times and he occasionally adopts a stilted, somewhat archaic style, but The Strangled Queen captures the grandeur of the epoch, tarnished as it was by intrigue, greed, ruthlessness, blind ambition and virtually every other vice you can imagine.

Thus, this description of Philip IV’s funeral in the Basilica of St. Denis: “The flames of thousands of tapers, arranged in clusters against the pillars, threw their wavering light upon the effigies of the Kings of France; ever and again the long stone faces seemed to assume the mobile expressiveness of a dream world, and one might have thought that an army of knights was sleeping an enchanted sleep in the middle of a flaming forest.”

Although Druon generally embraces a sober tone, The Strangled Queen is not without humor, and it displays more than a dash of cynicism. Describing the countless bone fragments and other dubious relics supposedly taken from the body of the late King Louis IX, a Catholic saint, Druon writes: “If all the pieces had been reassembled, the surprising discovery would undoubtedly have been made that the King-Saint had doubled in size since his death.”

The Strangled Queen proceeds at a slower place than The Iron King, the first entry in this series, but at 269 pages in paperback, this installment is not overly long, and it does build to a dramatic, if not especially surprising, climax. Suffice it to say that, based on what transpires in this novel, very dark storm clouds loom over the kingdom of France, as Druon’s series continues.