By Paul Carrier

I haven’t yet read A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin’s fantasy series. Nor have I watched HBO’s A Game of Thrones. But I know enough about both to realize that Martin is a wizard at spinning heart-pounding yarns bubbling with political intrigue, sexual escapades, dynastic power struggles, civil war, and all manner of mayhem and high drama.

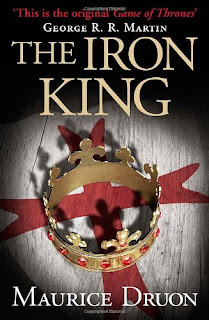

So when I learned that Martin has described The Accursed Kings, Maurice Druon’s series of historical novels, as “the original Game of Thrones,” I sat up and took notice.

A French novelist, Druon chronicled the downfall of France’s Capetian kings (who ruled from 987 to 1328) and the start of the Hundred Years War, in which England, France and their allies struggled for control of the French throne from 1337 to 1453.

The author, who died in 2009, published the series in French between 1955 and 1977. In translation, the novels are now attracting new fans on this side of the Atlantic, thanks in large part to Martin’s wholehearted praise.

In a forward to a recent English version of the first installment, The Iron King, Martin wrote that The Accursed Kings series “has it all. Iron kings and strangled queens, battles and betrayals, lies and lust, deception, family rivalries, the curse of the Templars, babies switched at birth, she wolves, sin, and swords, the doom of a great dynasty . . . .”

Druon’s series opens in 1314 when King Philip IV of France, a cold-eyed, shrewd and unbending ruler known as Philip the Fair (for his looks rather than any sense of justice) completes his seven-year quest to exterminate the powerful Knights Templar and confiscate their wealth. He closes that chapter of his reign by burning two leading Templars at the stake: Grand Master Jacques de Molay and Geoffrey de Charney.

Moments before his body is consumed by the flames, de Molay curses Philip; one of his top adminstrators, Guillaune de Nogaret; and Pope Clement V for conspiring to destroy the Templars. As Druon recounts it, de Molay, in a strong voice that carries far afield, summons his adversaries “to the Tribunal of Heaven before the year is out, to receive your just punishment.” Philip and de Nogaret look on as the dying de Molay vows: “Accursed! Accursed! You shall be accursed to the thirteenth generation of your lines.”

The curse becomes the stuff of legend when Clement and de Nogaret die soon after de Molay predicted their demise. The first to succumb is Clement, whose passing shakes Philip to the core. “His face was astonishingly pale” when he learned the news, Druon writes, “and within the long royal robe that covered his body he felt stiff with the icy rigor of death.”

Philip’s fear is reflective of the curse, but it’s not the only manifestation of it. Even as the king’s end draws near, scandal strikes his family. Philips’s daughter Isabella, queen of England by virtue of her marriage to King Edward II, discovers that the wives of two of her three brothers are adulterers. Isabella's third sister-in-law helped the other two women arrange their trysts.

The vengeful Isabella sails to France to convey the news to her father. The three cuckolded princes — weak, unimpressive men — are shattered to learn that their wives have betrayed them. And Philip’s rage knows no bounds. He forces his cheating and enabling daughters-in-law to watch the predictably gruesome executions of the two men involved in the illicit relationships, then imprisons all three of the princes’ wives — two of them, for life.

And that’s just for starters in the first of these seven novels.

It’s hard to say which aspect of The Iron King is the most rewarding: the vigorous plot, the well-drawn characters lifted from the pages of history, or Druon’s scholarship. (This is the first historical novel I’ve read that includes close to a dozen pages of numbered end notes.) The Iron King has the feel of a grand adventure yarn concocted by Alexandre Dumas (think The Three Musketeers, which is set in France some 300 years later), but written in a more contemporary style and with a greater emphasis on historical accuracy.

It’s hard to say which aspect of The Iron King is the most rewarding: the vigorous plot, the well-drawn characters lifted from the pages of history, or Druon’s scholarship. (This is the first historical novel I’ve read that includes close to a dozen pages of numbered end notes.) The Iron King has the feel of a grand adventure yarn concocted by Alexandre Dumas (think The Three Musketeers, which is set in France some 300 years later), but written in a more contemporary style and with a greater emphasis on historical accuracy.

No wonder Martin is a fan.

The Wall Street Journal did its part to boost Druon’s standing in this country with a story back in March that focused in part on his work. “There are murders galore in these books—one queen is strangled, one king poisoned and another thought to be poisoned while still a baby at his christening,” The Journal noted. “There is skullduggery, conspiracy and civil war. There are men of great ability and few scruples, and scarcely a page without dramatic incident.”