What a difference a decade makes.

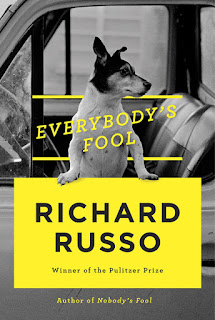

Damaged but determined, the denizens of North Bath, N.Y., stumble their way through Richard Russo’s latest novel, which takes place some 10 years after the tragicomic goings-on that made Nobody’s Fool such a humorous and touching read featuring many of the same characters.

Widowed teacher Beryl Peoples has passed on, leaving her large home to Donald “Sully” Sullivan, the likable but misguided protagonist of the earlier novel. Thanks to an unprecedented bit of good luck stemming in part from a big win at the off-track-betting parlor, the 70-year-old Sully has gone from cash-strapped odd-jobber to comfortable retiree.

Sully’s old boss, corner-cutting contractor and ladies’ man Carl Roebuck, is still around, but prostate surgery has left him incontinent and impotent, at least temporarily. Rub Squeers, Sully’s none-too-bright working partner in the previous novel, feels lost and listless now that Sully, whom he worships, doesn’t have much time for him anymore.

Ruth, a married woman who carried on with the divorced Sully for decades before they finally broke it off, now owns Hattie’s Lunch, the local diner and one of Sully’s hangouts. As for Doug Raymer, the hapless patrolman of Nobody’s Fool, he’s now the chief of police in North Bath, an aimless, barely competent cop made all the more miserable by the recent accidental death of his beautiful wife.

Russo gracefully explores the troubled, often disappointing lives of these small-town working stiffs (and assorted jobless slackers) with insight, affection and a healthy dollop of humor. Here, as in Nobody’s Fool, sharp verbal exchanges and pointed zingers leaven the quiet desperation that permeates so many lives.

Skilled storyteller that he is, Russo offers up a rollicking saga that will leave readers turning the pages for more. At the same time, though, Everybody’s Fool is a character-driven tale in which plot twists allow Russo to peel away the layers and delve into the interior lives of his creations. The end result is a telling peek into the workings of the human heart, with its fondness for deceit and self-deception.

There’s much angst to be found here, as people struggle, often with good humor, to make sense of their lives.

Raymer is plagued by feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem in Everybody’s Fool. Consumed by the knowledge that his late wife Becka was about to leave him for another man at the time of her death, Raymer is obsessed with identifying Becka's lover.

Ruth finds herself trapped in a loveless marriage to Zack, an overweight hoarder who has transformed their home, garage, yard and shed into an ever-growing collection of junk that Zack claims to be selling, piece by piece, at a profit. Roy Purdy, a twisted ex-con and Ruth’s former son-in-law, plots revenge against Ruth, Sully and others whom he sees as having wronged him.

As for Sully, his problems are particularly heartbreaking. A cardiologist at the VA hospital has told him he has no more than two years to live — maybe one. It’s a secret that preys on his mind and his body, but one that he refuses to share with anyone.

Secondary characters, only some of them human, make memorable appearances here, including Raymer’s black, highly opinionated, somewhat intimidating police dispatcher, Charice Bond; her debonair twin brother Jerome, a cop in nearby Schuyler Springs; and Sully’s dog Rub, named after Sully’s pal Rub. Dual Rubs trigger comic confusion when Sully gives commands to canine Rub in the presence of human Rub.

Most of the major characters in Everybody’s Fool are endearingly foolish, yet some find redemption in heartwarming ways. In a sense, Russo is telling us that there really are no walk-on parts, in literature or in life. For example, Raymer has gone from being an almost inconsequential buffoon in Nobody’s Fool to a complex character in the new novel. It’s all a matter of perspective.

“I love the idea of a character who seems to be a one-off or a joke or a functionary but then to be reminded that there are no small lives, there are no small stories, there are no small people,” Russo told The Wall Street Journal earlier this year. “Bit players don’t seem like bit players in their own lives. It’s an act of imagination that that life, which seemed small earlier, is something huge if you’re the person living it.”