By Paul Carrier

How far the kingdom has fallen.

At the start of Maurice Druon’s seven-part series of historical novels, known collectively as The Accursed Kings, Philip IV is the king of France. During his nearly 30-year reign, which ends with his death in 1314, France is the largest, wealthiest and most powerful nation in all of Europe.

But The Iron King, the first book in the series, witnesses the death of this tough-minded visionary. In the novels that follow, France falls into the hands of a sad collection of largely inept rulers who, in their mediocrity, chip away at Philip’s many accomplishments and leave France crippled and vulnerable.

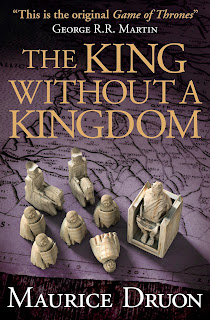

Now, in the closing seventh volume, The King Without a Kingdom, John II has assumed the throne. Mercurial, hot-headed and ill-equipped, the vengeful John, who is coronated in 1350, has a knack for making bad decisions at virtually every turn.

Brave but unskilled as a military leader, he is blind to his shortcomings. John changes his mind with dizzying frequency and makes critical decisions based on petty grievances, or rumor and hearsay. As Druon’s animated, sometimes peevish narrator, French cardinal Hélie de Talleyrand-Périgord, observes, “a greater fool than this king is not to be found . . . .”

Unfortunately for France, this is no time for feckless leadership.

The Hundred Years War, which England and France waged, off and on, for 116 years (1337-1453) to decide who would control France, was well underway by the time John came to power. France suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of Crécy in 1346, and England’s King Edward III captured Calais the following year. “Scarcely a year passes that he doesn’t land his troops on the continent,” Druon’s worldly, well-informed cardinal tells us.

England’s star is on the rise. Despite the country’s small population, made smaller still by the ravages of the plague, Edward III “had built a prosperous and feared nation” that was on a par with any in Europe. “The wool trade, maritime transport, the possession of Ireland, an effective exploitation of the abundant Aquitaine, royal powers exercised, and obeyed, everywhere, an ever-ready army forever at work; this is how England has become so strong and rich.”

Across the channel, the French king is disliked by his nobles. Rebellious French barons align themselves with England, whose armies plunder the French countryside at will. The French economy is a shambles. “When one allows prices of all commodities to rise out of all proportion while at the same time weakening the currency,” Talleyrand notes, “great unrest and reversals of fortune are inevitable. Setbacks, France has already witnessed, and it is now headed for ruin.”

Druon apprises the reader of the fate of great armies, but he is no French version of Bernard Cornwell, whose action-packed tales of warfare overflow with bloodcurdling war cries and battlefield heroics. The Accursed Kings is largely set in a world of court intrigue and political shenanigans. Violent, yes. (A botched beheading comes to mind.) But it’s mayhem on a personal scale, rather than a grand one, until Druon closes the novel by describing a climactic battle.

The Accursed Kings series offers a taste of the power the papacy exercised during this period, while acknowledging the limitations on that power as well. That is especially true in this novel. The Protestant Reformation was still many years away, but even in the mid 14th century there was growing skepticism about the wealth, opulence and corruption of the papal court, which at the time of The King Without a Kingdom was based in Avignon, France, rather than Rome.

The pope — in this case, Innocent VI — remained a major player on the European stage, which was, after all, a collection of Catholic nations. But the Avignon popes, all of whom were born in France, were viewed as allies of that kingdom, creating friction and distrust in their dealings with other nations.

Six years after John became king, England scored yet another major victory in 1356 at Poitiers, and it did so against all odds because French troops greatly outnumbered those of the English army. Druon portrays the buildup to this battle, and the battle itself, as the ultimate proof of John’s incompetence.

Druon, who died in 2009, ends his saga at Poitiers, but for the people of France, the ravishes of war were far from over. The English won what was arguably their greatest victory of the war almost 60 years later, at Agincourt in 1415. The tide finally began to turn in the years that followed, when Joan of Arc lifted the siege of Orléans and paved the way for Charles VII to be crowned king of France. By the time the war finally ended in 1453, France had regained most of the territory it had lost to England.