By Paul Carrier

In 1692, one of the most chilling episodes in American history unfolded in Massachusetts when “witches” descended on Salem. The wave of hysteria that followed afflicted children and adults and left the jails overflowing with suspects. Twenty witches (and warlocks), were killed, 19 of whom were hanged. (The 20th, Giles Corey, was crushed to death in a failed attempt to force him to confess.)

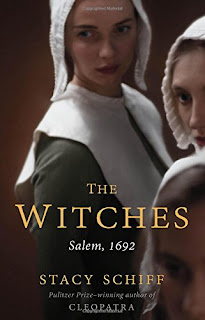

Historians by the dozen have chronicled this stain on colonial America. Now Pulitzer Prize-winner Stacy Schiff, whose books include a biography of Cleopatra, tackles the subject in a work of history that reads like a thriller and places the event in the larger context of life in 17th-century Puritan New England. Only late in the book does Schiff analyze possible causes; her main thrust is a page-turning narrative that tells the story of what happened over the course of nine crazed months.

Schiff’s wide-ranging account is so vivid that it almost literally transports the reader back in time. We see the writhing of the victims, hear the absurdly wild accusations and fanciful confessions, and marvel at the rigid fanaticism of judges who were more than willing to suspend disbelief in their zealous quest to suppress what they viewed as a reign of terror orchestrated by Satan.

Consider this passage, which describes accused witches Ann Foster and Martha Carrier (no relation) soaring over the countryside on a pole. (Not a broom.) “A plush carpet of meadows and hillocks unfurled beneath the women as they flew southeast across the Ipswich River, over red maples and blossoming orchards, the wind in their faces, a bright moon pasted in the sky,” Schiff writes, based on Foster’s account. “They traveled at high speed, covering in a flash ground that would have required three and a half hours by a good horse . . . .”

With compelling clarity, The Witches dispels many a myth.

No witches were burned in Salem. The Puritans, far from being a bland lot, were a gossiping, backbiting, litigious bunch of busybodies who often quarreled with their ministers and spent a goodly amount of time at the local taverns. There was as much animosity in the region, Schiff writes, “as there were mangy dogs and marauding pigs.”

Not all of the accusers were teenage girls, nor were all of the accused marginalized women. George Burroughs, who was convicted and hanged, was a Harvard-educated minister from Maine who had previously led the Salem Village congregation. Elizabeth Cary, accused but not executed, was married to a wealthy ship captain. Ann Dolliver, another suspected witch who survived, was the daughter, granddaughter and great-granddaughter of ministers. Eventually, even the governor’s wife was labeled a witch.

Nor was 1692 an otherwise tranquil time in Massachusetts. King Philip’s War, a devastating Indian war that wiped out a third of New England’s towns, had ended a mere 14 years earlier. Like other settlements in the region, Salem Village lived in constant fear of French and Indian attacks in a politically tumultuous colony whose charter had been revoked by England in 1684. Massachusetts forcibly removed the governor of the Dominion of New England in 1689, launching a period of instability. A new charter, and a new governor, did not arrive until the witch hunt was underway.

Turmoil and anxiety were the norm in that time and place.

Deeply researched and written with verve and energy, The Witches is disturbing on many levels, not least because it shows the credulity of well-educated judges and other respected citizens who should have known better. Skepticism, reason and logic were in painfully short supply in 1692 Salem, even when something as simple as common sense might have averted misguided conclusions.

Why, for example, did judges at the preliminary hearings conclude that screeching victims who suddenly fell silent during the public interrogation of a suspected witch had been struck dumb by the defendant, when it would have been more sensible to assume they had simply chosen silence? Why would suspected witches who insisted they were innocent undermine their case by practicing witchcraft while on trial, tormenting the girls who writhed and screamed before the court? And why were well-regarded women who were supported by reliable character witnesses convicted of witchcraft? The godly and elderly Rebecca Nurse was acquitted, but the verdict caused such pandemonium, including among the judges, that the jury eventually reversed itself without a compelling reason for doing so. Nurse was hanged.

In the end, we are left with the lingering question of why an entire region (the accusations extended beyond Salem) and all ranks of society seemingly descended into a collective madness. Theories abound. Schiff posits that several factors were at play, and they all hinged on one dangerously archaic idea: the firm Puritan belief in witchcraft.

The initial accusers, emotionally repressed girls living in a stiff-backed, strife-torn community, seem to have developed conversion disorder, which the Merriam-Webster dictionary defines as a psychiatric condition in which “bodily symptoms (as paralysis of the limbs) appear without physical basis and that is typically associated with psychological stress or conflict.”

As the accusations proliferated, otherwise sensible people nursing grudges or fearing for their own safety began pointing fingers too. Accusers tried to immunize themselves against charges of witchcraft by claiming they were victims, afflicted by others. Some suspects confessed, knowing that the court, in an amazingly bizarre twist, would spare confessors but convict those who professed their innocence. And the judges in the English colony were desperate to show suspicious authorities in England that Massachusetts was not a rebellious, lawless land, but a loyal colony governed by forceful and decisive officials.

It was, Schiff suggests, a deadly mix of several things: mental illness, superstition, autocratic religious orthodoxy and clear-eyed, deliberate lying by people who realized they had fallen down the rabbit hole. “If you could save your life by admitting that you flew through the air on a pole,” Schiff asks, “wouldn’t you?”