By Paul Carrier

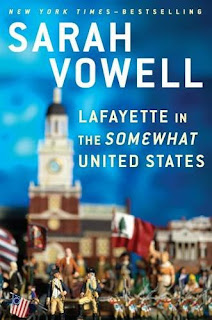

How best to describe Sarah Vowell, whose latest book, Lafayette in the Somewhat United States, hit the shelves this year?

Vowell is the author of several books dealing with history, although she probably would be the first to admit that she’s no historian, at least not in the traditional sense of that word. She blends travel, humor, journalism and analysis, marrying history, pop culture and personal anecdotes to bring the past to life in a manner that can be laugh-out-loud funny one minute and deeply moving the next.

Lafayette in the Somewhat United States covers a lot of ground, examining the marquis’ youth and upbringing in France, his arrival in America, his role as a general in the Continental Army, and his unflagging devotion to George Washington. But this slim volume also provides context, by pulling back from Lafayette to explore the revolution as a whole. It's a meandering review, yet one that always works its way back to the roles played by Lafayette and the nation of his birth.

“I write books for the general reader; I’m not some kind of scholar,” Vowell said in an interview posted on americanlibrariesmagazine.org. “Knowing that for some of my readers this is going to be the only book they read on the revolution, I think it kind of broadened the scope of the book a little bit.”

That scope is broad indeed. One of Vowell’s trademarks is her fondness for digression, and that’s on display here.

For example, Vowell’s recap of the Battle of Monmouth (in New Jersey) works in asides on Bruce Springsteen and the George Washington Bridge lane-closure scandal (aka Bridgegate) that has undermined the credibility of N.J. Gov. Chris Christie. So if you find linking the seemingly unlinkable off-putting, Vowell may not be for you.

A central theme of the book is Vowell’s claim that Americans always have been, as we certainly are now, naturally contentious. Yet Lafayette was, in his lifetime, a genuine and universally admired American hero. Vowell recounts the wildly enthusiastic reception Lafayette received during a triumphal return visit to the United States in 1824-25, by which time he was the last surviving general of the Continental Army and a living symbol of the alliance with France that secured American independence.

Vowell explains that Lafayette’s appeal stems in large part from the fact that he was something rare in our history and politics: a unifying force. “Other than a bipartisan consensus on barbecue and Meryl Streep, plus that time in 1942 when everyone from Bing Crosby to Oregonian schoolchildren heeded FDR’s call to scrounge up rubber for the war effort, disunity is the through line in the national plot,” Vowell writes, “not necessarily as a failing, but as a free people’s privilege.”

France’s role in securing America’s freedom gets special attention from an admiring Vowell, who explains that Louis XVI sent a mountain of supplies to the patriots even before France formally recognized the rebels and entered the war. Especially memorable is Vowell’s retelling of the Battle of Yorktown, where French forces actually outnumbered the Americans. If there is a great unsung hero of the revolution, a forgotten player whose decisions at Yorktown effectively gave the United States its independence, it is François Joseph Paul de Grasse, the French admiral whose massive and powerful fleet bottled up the British army at Yorktown.

Americans celebrate Independence Day rather than Yorktown Day, Vowell writes, because even though we broke with Great Britain on our own initiative, it was France that won our revolution for us. “Who wants to barbecue a hot dog and ponder how we owe our independence to the French navy?” Vowell writes.

Vowell’s always-entertaining irreverence, which has long been one of the highlights of her take on history, shines through in her latest book. Witness her assessment of the decision by the Continental Congress to commission the inexperienced 19-year-old Lafayette as a major general after he offered to serve in the Continental Army without salary.

The Continental Congress “had its doubts about saddling General George Washington with a teenage French aristocrat,” Vowell writes, “but Ben Franklin wrote from Paris that the kid might be of use and, what the hell, the price was right.”