By Paul Carrier

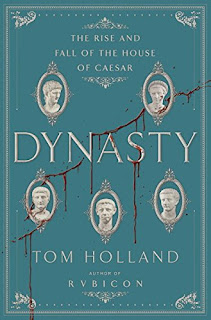

In 2005, British historian Tom Holland released Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic. Now Holland picks up where he left off with Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar, which focuses on the first five emperors — the Julio-Claudians — who ruled Rome following the assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March in 44 BC: Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero.

It’s a tale of autocratic rule and resistance, nobility and depravity, set in a burgeoning empire that was at once principled and barbaric. The 21st-century reader will recognize some of our own virtues and vices at play in a world that seems quite foreign, but not entirely alien.

Dynasty quickly summarizes the period preceding the birth of the empire, including Rome’s founding, its early monarchy, the creation of the republic, and the epic struggle that saw Augustus emerge victorious over Marc Antony. Then Holland settles in for the task at hand, an exploration of the five emperors who might well be described as the most famous -- and in two cases, infamous -- of the lot.

What makes Holland’s account so compelling is that he offers far more than a simple chronological retelling of who did what when. Holland examines the whys and wherefores of the events that transpired during this period, and he delves into the character, style and motives of the key players. Psychology lies at the heart of this account.

In this elegantly written history, Holland sketches fascinating portraits of the period’s legends and lesser lights, putting his analytical skills and his eye for telling details to good use. Thus we learn that Augustus was “a hopeless general” but a shrewd and highly successful politician who camouflaged his lust for power. His eyebrows “met above his nose,” he had bad teeth and he was so anxious about his height that he wore platform heels. It was said that he “smoothed his legs by singeing off their hairs with red-hot nut shells,” which struck the Roman people as effeminate behavior.

The brooding, ultimately debauched, Tiberius, perhaps the greatest general of his generation, was beloved by his men yet a stiff and awkward elitist “profoundly uncomfortable in his own skin” when he found himself thrust upon the political stage. He was “tall, muscular, and well-proportioned,” with piercing eyes and a fashionable mullet, but he also had a recurring case of adult acne. Pimples “would suddenly erupt all over his cheeks in a violent rash.”

Caligula was a “connoisseur of suffering” with a malicious sense of humor. He despised the aristocracy, including the Senate, and openly trumpeted what Augustus and Tiberius had tried to hide: that the republic was dead. In Holland’s telling, Caligula was more cynical and sadistic than mad. When he threatened to make his favorite horse a consul, he did so to show his disdain for Roman tradition, not because he was insane.

Scorned by his own family as “a twitching, dribbling cripple,” Claudius had his first wife, Messalina, assassinated, and may have been murdered by his second wife, Agrippina. Despite his physical handicaps, he was a knowledgeable student of Roman history and a far from unsuccessful emperor who made spectacular investments in infrastructure and “looked more fondly on the plebs” than did his haughty and aloof predecessor.

Flamboyant, amazingly theatrical and completely self-absorbed, Nero had his mother and his first wife killed, but later showed enough sense to send a conciliatory commander to Britain after Rome subdued a bloody revolt there. He kicked his second wife, the pregnant Poppaea Sabina, to death, and later married a eunuch who was trained to emulate Poppaea’s looks. Did he set Rome ablaze in 64 AD, and play his lyre while the city burned? We’ll never know, but such rumors were widespread during his lifetime.

The secondary players -- and there are many -- are just as well-drawn. Antony was “corrupted by the soft temptations of the East” and took to urinating in a golden chamberpot. The hipster poet Ovid was a fashionista and womanizer. Livia, wife of Augustus, mother of Tiberius, was a very real power behind the throne. Tiberius’ nephew Germanicus proved to be a bold but reckless and ill-fated general. Messalina was “carnivorous, irresponsible and heedless of every risk,” a woman whose very name became a Roman synonym for nymphomania.

Holland obviously revels in the telling of his tale, exploring the early decades of the empire with verve, insight and narrative energy. This is ancient Rome at its most human, full of emotion, energy and personality. The empire's many facets — cultural, military, political, religious, social, architectural, sexual — come under scrutiny here. Digressions, anecdotes and myths provide offbeat, but memorable, bits of information. For example, the Romans discovered a “curious concoction” in Germany that was made of goat lard and ashes: soap. And it was said that an eagle dropped a white chicken, unharmed, into Livia’s lap, which was interpreted as a portent that she would control her husband, Augustus.

The record of the five emperors from the House of Caesar was “painted in blood and gold,” Holland writes, “a thing of mingled wonder and horror.”