By Paul Carrier

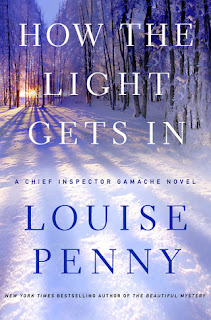

Books are published at such an astonishing rate that readers are never without something new to anticipate. Canadian author Louise Penny'a latest was high on my list of "can't wait" books this year as I prepared to embark on yet another outing - the ninth - with Chief Inspector Armand Gamache of the Sûreté du Québec, the provincial police force in that French-speaking Canadian province.

How the Light Gets In has its charms, not least because relationships that are key parts of the series evolve and mature. In the end, though, this one is a disappointment.

Principled, shrewd and sophisticated, Gamache has run the department's homicide division for years. But his career is in jeopardy from the opening pages of How the Light Gets In, thanks to a long-running feud with his vindictive and unscrupulous boss, Chief Superintendent Sylvain Francoeur, who is hatching a mysterious plot that is clearly diabolical.

There is, of course, a murder to be solved here as well. Predictably, it brings the Montréal-based Gamache to the isolated village of Three Pines, in Québec's Eastern Townships. Several of Penny's novels have been set in Three Pines, a bucolic gem whose endearingly quirky residents seem to have withdrawn from the world at large. Except, of course, when murder rears its head, as it often does there.

The case at hand involves the death of a woman in her 70s who used the pseudonym Constance Pineault to disguise her real identity: Constance Ouellet. Ouellet, it turns out, was the last of the Oullet quintuplets, five twins whose fame spread around the globe before they secluded themselves in an obsessive quest for privacy.

Ouellet had recently visited Three Pines and is packing for a return trip when she is killed in her Montréal home. Was her murder a random act? Or did it involve her high-profile background and upbringing?

Penny admits, in an author's note, that the fictional Ouellet "quints" were inspired by the real-life Dionne quintuplets, who were born in Ontario in 1934 and became the first quintuplets known to have survived infancy. But the author takes pains to point out that the lives (and deaths) of the Oullet siblings are in no way based on those of the Dionne sisters, two of whom were still living as of May 2013.

Solving the puzzle of Ouellet's death is one of two central plot lines in How the Light Gets In. For fans of the Gamache series, the murder may be less compelling than the chief inspector's struggle with the dark forces that now control the Sûreté. The added spice of Gamache's fight for his professional survival, and possibly even his life, is what elevates the plot beyond that of a simple murder mystery.

We quickly learn that Francoeur has gutted Gamache's homicide division and filled its vacancies with lackeys who disdain him. To make matters worse, the rift that developed in a previous novel between Gamache and his beloved deputy, Jean-Guy Beauvoir, has worsened, leaving Beauvoir shattered and drug-addled and Gamache adrift in a treacherous sea. His new right hand, Isabelle Lacoste, is his only surviving ally in homicide.

Francoeur, it turns out, is after far more than Gamache's destruction. In fact, Gamache is merely an obstacle in Francoeur's path as he and his powerful but initially unidentified master put the finishing touches on a much larger conspiracy.

Penny's plotting, and the enthralling voice of her novels, are impressive. But Francoeur's nefarious goal, once it is revealed, is implausible, and on more than one level. Still, Penny's recurring characters, human and otherwise, remain endearing, right down to an irascible pet duck named Rosa and Henri, Gamache's lovable but none-too-bright German Shepherd.

Henri's head "seemed simply a sort of mount" for his big ears, Penny writes. "Fortunately Henri didn't really need his head. He kept all the important things in his heart."

Principled, shrewd and sophisticated, Gamache has run the department's homicide division for years. But his career is in jeopardy from the opening pages of How the Light Gets In, thanks to a long-running feud with his vindictive and unscrupulous boss, Chief Superintendent Sylvain Francoeur, who is hatching a mysterious plot that is clearly diabolical.

There is, of course, a murder to be solved here as well. Predictably, it brings the Montréal-based Gamache to the isolated village of Three Pines, in Québec's Eastern Townships. Several of Penny's novels have been set in Three Pines, a bucolic gem whose endearingly quirky residents seem to have withdrawn from the world at large. Except, of course, when murder rears its head, as it often does there.

The case at hand involves the death of a woman in her 70s who used the pseudonym Constance Pineault to disguise her real identity: Constance Ouellet. Ouellet, it turns out, was the last of the Oullet quintuplets, five twins whose fame spread around the globe before they secluded themselves in an obsessive quest for privacy.

Ouellet had recently visited Three Pines and is packing for a return trip when she is killed in her Montréal home. Was her murder a random act? Or did it involve her high-profile background and upbringing?

Penny admits, in an author's note, that the fictional Ouellet "quints" were inspired by the real-life Dionne quintuplets, who were born in Ontario in 1934 and became the first quintuplets known to have survived infancy. But the author takes pains to point out that the lives (and deaths) of the Oullet siblings are in no way based on those of the Dionne sisters, two of whom were still living as of May 2013.

Solving the puzzle of Ouellet's death is one of two central plot lines in How the Light Gets In. For fans of the Gamache series, the murder may be less compelling than the chief inspector's struggle with the dark forces that now control the Sûreté. The added spice of Gamache's fight for his professional survival, and possibly even his life, is what elevates the plot beyond that of a simple murder mystery.

We quickly learn that Francoeur has gutted Gamache's homicide division and filled its vacancies with lackeys who disdain him. To make matters worse, the rift that developed in a previous novel between Gamache and his beloved deputy, Jean-Guy Beauvoir, has worsened, leaving Beauvoir shattered and drug-addled and Gamache adrift in a treacherous sea. His new right hand, Isabelle Lacoste, is his only surviving ally in homicide.

Francoeur, it turns out, is after far more than Gamache's destruction. In fact, Gamache is merely an obstacle in Francoeur's path as he and his powerful but initially unidentified master put the finishing touches on a much larger conspiracy.

Penny's plotting, and the enthralling voice of her novels, are impressive. But Francoeur's nefarious goal, once it is revealed, is implausible, and on more than one level. Still, Penny's recurring characters, human and otherwise, remain endearing, right down to an irascible pet duck named Rosa and Henri, Gamache's lovable but none-too-bright German Shepherd.

Henri's head "seemed simply a sort of mount" for his big ears, Penny writes. "Fortunately Henri didn't really need his head. He kept all the important things in his heart."